THE COUNTERFEITERS - NAZI PERIOD REVISITED

Under the skin of the cultural beast

Alice Munro's work eluded me until her newest work, The View From Castle Rock. It's a trusim that great writers teach you how to read their work, they insist on it, you must succumb to their particular prose and once conquered, you're conquered. Her work at times is arguably flawed -- particularly in this fascinating collection of stories drawn from letters, chronicles, and evidence of her family dating back to their migration from the darkest forms of Calvinism in Scotland in the eighteenth century, chronicling their struggles across the Atlantic into the present. The tales are at times brutal, at times poignant, uncompromising and unsentimental in their grittiness of the stark harshness of the life that was left and the new stark reality of eking out an existence in a world where the streets are not paved with gold.

Alice Munro's work eluded me until her newest work, The View From Castle Rock. It's a trusim that great writers teach you how to read their work, they insist on it, you must succumb to their particular prose and once conquered, you're conquered. Her work at times is arguably flawed -- particularly in this fascinating collection of stories drawn from letters, chronicles, and evidence of her family dating back to their migration from the darkest forms of Calvinism in Scotland in the eighteenth century, chronicling their struggles across the Atlantic into the present. The tales are at times brutal, at times poignant, uncompromising and unsentimental in their grittiness of the stark harshness of the life that was left and the new stark reality of eking out an existence in a world where the streets are not paved with gold.

than in Faulkner that place is everything. The slow, languid pace of the backwater of Mississippi, spanish Moss, ruined plantations, the ineluctable smell of the vanquished permeate every page of his work. I recently read As I Lay Dying for the tenth time, and it held up. If place is all, this is as good as it gets.

than in Faulkner that place is everything. The slow, languid pace of the backwater of Mississippi, spanish Moss, ruined plantations, the ineluctable smell of the vanquished permeate every page of his work. I recently read As I Lay Dying for the tenth time, and it held up. If place is all, this is as good as it gets.

.

.  Mary Gaitskill isn't kidding around. Freud's famous maxim -- the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego -- has rarely been taken to such a successful extreme by any writer of contemporary fiction. Her willingness to expose, confront, and engage the body in her swirling narrative of memory, perversion, desire, death and triumph brings in all the big themes of literature without sentimentality, and with an unfaltering quest to seek out the good, the bad, and the ugly of sexuality and our culture in a way that makes the likes of Philip Roth and John Updike seem

Mary Gaitskill isn't kidding around. Freud's famous maxim -- the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego -- has rarely been taken to such a successful extreme by any writer of contemporary fiction. Her willingness to expose, confront, and engage the body in her swirling narrative of memory, perversion, desire, death and triumph brings in all the big themes of literature without sentimentality, and with an unfaltering quest to seek out the good, the bad, and the ugly of sexuality and our culture in a way that makes the likes of Philip Roth and John Updike seem absolutely inhibited. Again to consider Freud: The pervert does what the neurotic envies: Gaitskill's writing is pervese where Roth and Updike by comparison are neurotic. She takes it a step further while avoiding the trap of an adolescent cultivating shock value for its own sake. Gaitskill belongs to the realm of Goya, Pasolini, and Diane Arbus in her fearless willingness to delve into the taboo without judgment. She exposes excrement, sadomasochism, desperation, disease, and excavates the delicate pulsating sublime pulsating within it all.

absolutely inhibited. Again to consider Freud: The pervert does what the neurotic envies: Gaitskill's writing is pervese where Roth and Updike by comparison are neurotic. She takes it a step further while avoiding the trap of an adolescent cultivating shock value for its own sake. Gaitskill belongs to the realm of Goya, Pasolini, and Diane Arbus in her fearless willingness to delve into the taboo without judgment. She exposes excrement, sadomasochism, desperation, disease, and excavates the delicate pulsating sublime pulsating within it all.

There is no positive addiction like being seduced by a book. And it seems to me that a decade is a crucial time in the lifespan of a book -- has it become merely a product, is it ready to be discarded -- or after ten years does it retain a certain kind of magic, that demands to be read and then read again, each time unfolding different nuances of meaning. I think aside from some of the negative reactions to the novel -- the lack of a successful ending, the lack of differentiation of some of the characters -- the immensity of its ambition to wed philosophy and

There is no positive addiction like being seduced by a book. And it seems to me that a decade is a crucial time in the lifespan of a book -- has it become merely a product, is it ready to be discarded -- or after ten years does it retain a certain kind of magic, that demands to be read and then read again, each time unfolding different nuances of meaning. I think aside from some of the negative reactions to the novel -- the lack of a successful ending, the lack of differentiation of some of the characters -- the immensity of its ambition to wed philosophy and poetry, its constant level of observation which is woven into the fabric of the drama remains a triumph. I keep finding sections that bear not only re-reading but which make me want to go back into philosophy and really plumb the depths of Hegel and Husserl. For those of you who want to go to the distance with serious writing that aims high but also shoots for life outside of the coterie audience of academia, Fugitive Pieces is a must and Michaels' poetry, largely unknown outside of her native Canada, holds the mark with the best of Adrienne Rich and Robert Lowell. If ever a book shows the value of ten years worth of writing, this one does.

poetry, its constant level of observation which is woven into the fabric of the drama remains a triumph. I keep finding sections that bear not only re-reading but which make me want to go back into philosophy and really plumb the depths of Hegel and Husserl. For those of you who want to go to the distance with serious writing that aims high but also shoots for life outside of the coterie audience of academia, Fugitive Pieces is a must and Michaels' poetry, largely unknown outside of her native Canada, holds the mark with the best of Adrienne Rich and Robert Lowell. If ever a book shows the value of ten years worth of writing, this one does.

Michael Ondaatje haunts me. The lyrical intensity of his prose finds the right level, the delicate balance between earth and ether. His novels are big in the best sense of literary ambition -- the psychological intensity of Shakespeare pitted against the power of the sentence that aspires and frequently achieves the level of intensity of Joyce or Woolf. So curious to see what his next novel will deliver.

Michael Ondaatje haunts me. The lyrical intensity of his prose finds the right level, the delicate balance between earth and ether. His novels are big in the best sense of literary ambition -- the psychological intensity of Shakespeare pitted against the power of the sentence that aspires and frequently achieves the level of intensity of Joyce or Woolf. So curious to see what his next novel will deliver.

It's been twenty years since Jeanette Winterson stunned the literary world with Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. I recently finished The Passion and found it curiously flat. It was as if the story had driven the engine of the experience so completely, that in the words of Virginia Woolf "the text failed to vibrate." I find this question so intriguing: what creates a Picasso or a James Joyce who push the edges of anartform incessantly, constantly expanding the envelope, right up until their deaths. And what creates an artist who makes a stunning debut but devolves from that point of origin into a product? All ideas on this welcomed.

It's been twenty years since Jeanette Winterson stunned the literary world with Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. I recently finished The Passion and found it curiously flat. It was as if the story had driven the engine of the experience so completely, that in the words of Virginia Woolf "the text failed to vibrate." I find this question so intriguing: what creates a Picasso or a James Joyce who push the edges of anartform incessantly, constantly expanding the envelope, right up until their deaths. And what creates an artist who makes a stunning debut but devolves from that point of origin into a product? All ideas on this welcomed.

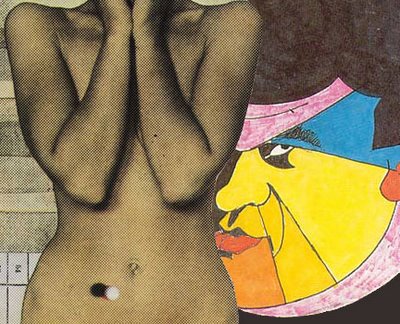

Check out where I went this weekend. These pictures by Janice Sloane, a long time legendary underground guerilla girl of the East Village really got me thinking.

Check out where I went this weekend. These pictures by Janice Sloane, a long time legendary underground guerilla girl of the East Village really got me thinking.

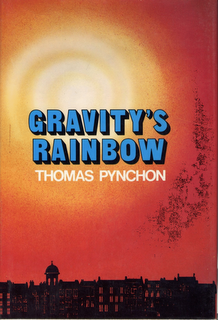

THOMAS PYNCHON REVISITED? Writing and culture always reflect back the world from which it emerges. Back in the derangement of 1973 a world filled with urnest -- the Watergate scandal, the American political system falling apart, the beginning of the end of Viet Nam, we had two odd cultural phenomenon. The Exorcist - a film where a pubescent girl played by the then-adorable Linda Blair screamed obscenities and defied the growing techno-secular world to enter her bedroom and chase the demons out screaming.

THOMAS PYNCHON REVISITED? Writing and culture always reflect back the world from which it emerges. Back in the derangement of 1973 a world filled with urnest -- the Watergate scandal, the American political system falling apart, the beginning of the end of Viet Nam, we had two odd cultural phenomenon. The Exorcist - a film where a pubescent girl played by the then-adorable Linda Blair screamed obscenities and defied the growing techno-secular world to enter her bedroom and chase the demons out screaming.

But here we are in 2006, in an age where despite the fact that more than 800 million Americans are in reading groups, Thomas Pynchon has put out a new novel which is actually accessible. I'm not sure whether to applaud him for trying to really reach an audience outside of the ivory tower, or whether this is a moment of despair, of giving up that rare form of high art in the service of pandering to the masses....?